- The WBC ordered Canelo and Yildirim to fight for the vacant belt. Soon it changed its mind and allowed Smith vs. Canelo to be for the title instead. Yildirim is a second- or third-tier fighter who was stopped in three rounds by Chris Eubank Jr. In 2017 but had been competitive with Dirrell in 2019.

- Watson completed at least Canelo Alvarez vs Avni Yildirim two passes to nine different players last Sunday, with three amassing at least 80 yards. Brandin Cooks led the way with 85 on four receptions, while Will Fuller V had a game high-tying six catches for 80, raising his team-leading total to 708 yards.

If Canelo Alvarez is on the road to becoming the undisputed super middleweight champion, then Avni Yildirim was merely roadkill.

Daniel Jacobs (born February 3, 1987) is an American professional boxer. He is a two-time middleweight world champion, having held the IBF title from 2018 to 2019 and the WBA (Regular) title from 2014 to 2017. Nicknamed the 'Miracle Man,' Jacobs' career was almost cut short in 2011 due to osteosarcoma, a rare form of bone cancer.

That was the inevitable result from the moment the World Boxing Council imposed Yildirim as the mandatory challenger to its title. Canelo is a diesel-powered 18-wheeler barreling down the highway. Yildirim stood in his path but did little else, intimidated and immobilized, hopeless and helpless. Canelo defeating Yildirim with ease was a foregone conclusion. Yildirim was gone before the fourth round could start.

In reality, the fight was over before it began.

This was like a bathroom stop on Canelo’s trek toward capturing all four major world titles. It’s unpleasant, stinks and takes up valuable time, but it’s necessary for getting to your destination without further interruption.

And so Canelo and his team sought to reframe this mismatch — presenting the inevitable as an infomercial.

This was far from the first time that a fighter used one bout as a blatant prelude for the next, which is smart business and storytelling in a sport that lacks a league and a fixed schedule.

It’s not even the first time Canelo did so. His lopsided beatdown of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. was barely over — though that, too, was over before it began — when it became clear that boxing fans had essentially purchased an expensive commercial.

“Golovkin, you are next, my friend,” he said in his post-fight interview, and the arena lights dimmed before he even finished his sentence, setting up a short video package, the opening licks of “Seven Nation Army” by The White Stripes, and the entrance of a suited, smiling Gennady Golovkin.

This time, fans already knew that Canelo would be facing Billy Joe Saunders in May. They were just awaiting the official announcement.

Canelo’s victory over Callum Smith last December had earned him Smith’s World Boxing Association title and Ring Magazine championship, as well as the vacant WBC belt. Saunders was the logical next move, an undefeated British fighter who holds the World Boxing Organization title, is promoted by Eddie Hearn’s Matchroom Boxing and is featured on DAZN. Canelo has a working relationship with the promoter and streaming service.

He’d inherited an obligation — a fight with Yildirim.

Yildirim hadn’t fought in two years, and yet the WBC said he deserved a second shot at its belt. The first one came in that last fight, when Yildirim met Anthony Dirrell for a vacant title. It had been stripped from David Benavidez after he’d come up positive for cocaine in an out-of-competition test.

Dirrell won a close, split technical decision that night when the fight was stopped early due to a bad cut over his left eye from an accidental head butt. Yildirim appealed for a rematch and was granted the opportunity. But Dirrell would go on to be stopped by David Benavidez later in 2019. Days later, it was announced that Yildirim had tested positive for two banned substances. The WBC soon announced that he’d been cleared of wrongdoing.

Benavidez-Yildirim was expected to take place in 2020. Then the coronavirus pandemic scuttled live boxing for several months. Benavidez returned to the ring last August but came in overweight for his first defense, losing the title on the scales. The WBC ordered Canelo and Yildirim to fight for the vacant belt. Soon it changed its mind and allowed Smith vs. Canelo to be for the title instead.

Yildirim is a second- or third-tier fighter who was stopped in three rounds by Chris Eubank Jr. in 2017 but had been competitive with Dirrell in 2019. The fact that Canelo had to face him or give up the title was doubly problematic. Canelo is clearly one of the best fighters in the world while Yildirim most definitely is not. That made Yildirim seem even more undeserving of sharing the ring with Canelo, something that had come about more by accident than accomplishment. And this mismatch was standing in the way of more important fights.

The WBC had made this mess, but Canelo cleaned it up. He easily swatted away this pesky situation, knowing he would have little trouble taking care of Yildirim, and that the only buzz remaining would be for what comes next.

Canelo often fights just twice a year, on weekends traditionally associated with major boxing pay-per-views: on or around Cinco de Mayo in May, and on or around Mexican Independence Day in September. As much of a mismatch as this was destined to be, it felt less offensive once Canelo scheduled it for February on DAZN, his second fight in the span of 70 days. It wouldn’t delay the Saunders fight, taking place another 70 days later in May, barring a bad cut or a huge upset.

A fighter who typically fights twice a year would be appearing three times in the span of five months, with two of those fights coming against two of the top super middleweights.

Photo by Mandatory Credit: Ed Mulholland/Matchroom.

This was a case of making the best of a bad situation.

This was going to be a squash match with little suspense beyond when and how it would end.

This was a showcase for Canelo, another chance for him to show off his impressive arsenal on offense and abilities on defense.

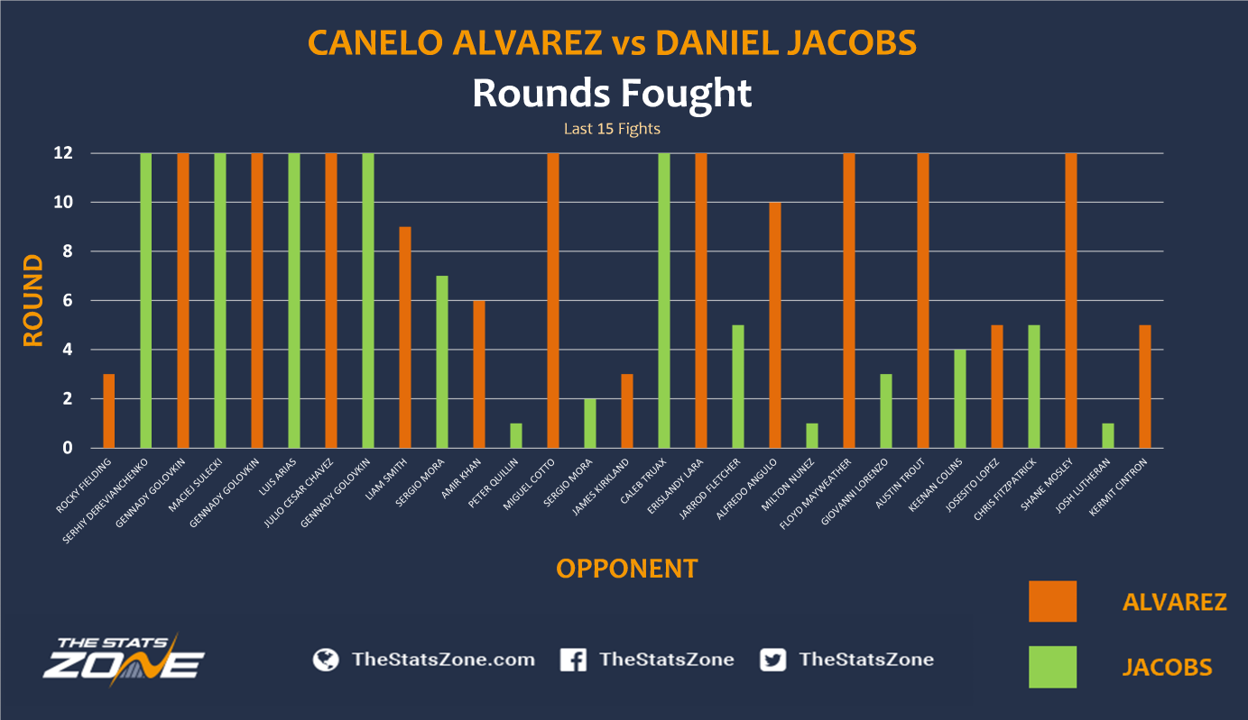

Daniel Jacobs Vs Canelo Predictions Bleacher Report

This was a show put on Saturday night in front of an announced crowd of 15,000. These were fans who could presumably be socially distant within the spacious pro football stadium outside of Miami, a large metropolitan area where major boxing matches are rarely held. They had bought tickets to see Canelo, no matter the opponent. His entrance included fireworks and a performance from popular musical artist J Balvin, providing more bang for the buck beyond a brief, one-sided beating and a decent undercard.

J Balvin’s performance and Canelo’s entrance lasted nearly as long as the fight itself.

Given his circumstances, Canelo opened up more than usual.

Given his circumstances, Yildirim shut down.

One fighter looked terrific. The other fighter looked terrified. The way Yildirim felt affected the way he fought. He never had a chance anyway. But this was making a bad situation worse. The pre-fight predictions had expected Yildirim to at least put up more resistance before being put away. Yildirim barely showed up. That allowed Canelo to show off.

Canelo both played with Yildirim and pounded him. He feinted with a right hand and instead threw a lead left uppercut. He thudded left hooks and right hands into Yildirim’s body in Round 1. He went 16 of 35 in the first round, according to CompuBox, including 13 of 15 with his power punches, a ridiculous 87 percent connect rate.

Yildirim, who’d averaged nearly 70 punches per round in the Dirrell fight, barely let his hands go and rarely committed to his shots. That, combined with Canelo’s defensive savvy, limited the challenger to landing just one punch out of the 29 he threw in Round 1. It was a jab.

Canelo’s body shots in the first round set up what came in the second round. The head shots began to pour forth in Round 2, beginning with a left hook and right uppercut, and continuing on with an exhibition of Canelo’s impressively varied arsenal.

A left hook pushed Yildirim back a step. A hook to the body was followed shortly thereafter by a hook to the head. Canelo would use a feint or a jab to set up his uppercuts. He moved back a step to dodge Yildirim’s left hook and then easily retaliated with a one-two combination. He stood forehead to forehead with Yildirim, teasing with a pair of right uppercuts to distract from the left hook to the body that followed. He turned his body to dodge a right cross and then turned back in one motion to counter with a right uppercut.

Yildirim didn’t do much of anything to deter Canelo. Instead, Yildirim merely kept his guard up high, almost as ineffective at stopping his opponent’s punches as he was at landing his own.

Canelo went 20 of 60 in Round 2, including 17 of 31 with power punches. Most of his missed blows were jabs. That was fine. The jabs largely served to set up other shots. Yildirim was credited with going 6 of 51 in Round 2. Almost all of his attempts came as jabs (4 of 42) instead of power punches (2 of 9).

Trainer Joel Diaz pushed for Yildirim to do more with the jab, or rather to do better with it, and to follow up with power punches. Diaz asked for him to block and counter. In other words, not just to stand there and let Canelo do whatever he wanted to do at his own pace.

“No respect to this guy,” Diaz said before Round 3 began.

Diaz was doing his job but was trying in vain. The greatest of pep talks still wouldn’t have made a difference.

Canelo had so much power on his punches that Yildirim blocked a hook early in the third and still was moved a step. The hard hooks around and through Yildirim’s guard continued to find their mark. After looping a right hand around Yildirim’s glove about a minute into Round 3, Canelo followed up with a one-two between the gloves that caught Yildirim by surprise. He fell backward and onto his right side, up before the referee reached the count of three.

Canelo opened up even further. He drove Yildirim to the ropes, threw three right crosses and two right uppercuts. Yildirim landed a left hook and Canelo kept coming as if nothing had happened. Canelo continued to pot-shot Yildirim, not trying to force the knockout, not trying to fell a tree with one swing, but rather chopping away deliberately, destructively.

Facing little resistance, and nothing he couldn’t handle, Canelo was throwing more and landing more with each subsequent round. He was 31 of 73 in Round 3, including 28 of 53 with power shots. Yildirim had done even less in the third than he had in the second, going 4 of 25 overall, landing 2 of 8 power punches.

After three rounds, Canelo had outlanded Yildirim by a total of 67 to 11, punishing him with 58 power punches while Yildirim had only scored with four.

“You all right?” Diaz asked after Round 3. “I’m going to give you one more round, Avni. If I don’t see you work, I’m going to stop you. You got to show me something. I’m here to take care of you. I’m giving you one more fucking round. If you’re not showing me that you’re OK, I’m going to stop you. Understand? You all right? You OK?”

Yildirim’s team couldn’t have liked what they saw in the ring and heard in the corner — or rather what they didn’t see, didn’t hear.

This was not going to end well for their fighter. And so they ended it themselves. There would be no highlight-reel, one-punch knockout like Canelo had scored against James Kirkland in 2015 and Amir Khan in 2016. As anticlimactic a conclusion as this was for fans, it was the right call. Yildirim wasn’t fighting like a warrior who wanted to go out on his shield. He wasn’t capable of going to war or shielding himself.

“Canelo is too good,” said Yildirim’s promoter, Ahmet Oner, in a backstage interview with iFL TV. In essence, he said, Yildirim had frozen under the pressure of fighting on such a big stage and against such a great opponent.

“We are not a boxing nation,” said Oner, who like Yildirim is originally from Turkey. “For our guys, it’s too tough to go [to] big arenas, music, walk-in. It’s not usual in Turkey. It’s not existing. And then you fight a huge superstar with punching power. So it’s too much for a boy like Avni. But he wanted to be a superstar. He fought now a superstar. He felt like a superstar. But Canelo is a superstar.”

Canelo is indeed a superstar — one of the most accomplished and most popular active fighters in the sport. He won world titles at junior middleweight, suffering his only defeat as a 23-year-old against one of the best boxers ever, Floyd Mayweather Jr, in 2013.

Canelo, now 30, has improved significantly since then. He earned the lineal middleweight championship from Miguel Cotto in 2015, then fought two closely contested, hotly debated matches with the fighter considered to be the best 160-pounder in the world, battling to a draw with Gennadiy Golovkin in 2017 and then winning a razor-thin decision in their 2018 rematch.

He defended the championship against Daniel Jacobs in 2019, then moved up two weight classes to demolish Sergey Kovalev for a light heavyweight world title later that year. He dropped down to super middleweight, completely outclassing the de facto number one 168-pounder, Callum Smith, last December.

He’s held world titles in four weight classes. He has two title belts right now at 168. Within the span of a year, he could wind up with all of them.

A video for the Saunders fight played during Canelo’s post-fight interview. It was but a brief commercial for the May 8 match, given that the preceding fight had served the same purpose.

Saunders is a mobile, capable boxer who previously held a title at middleweight, dethroning Andy Lee and then making three successful defenses. His reign at super middleweight hasn’t been overly notable, both in who he’s faced and how he’s looked.

A victory over Canelo would obviously change that. Saunders presents a different set of skills than Canelo’s recent run of opponents. He’ll need to box brilliantly to win. That’s not a given, especially given that Canelo is far better than anyone Saunders has ever faced.

If Canelo wins in May, then he would presumably try to make a fight with Caleb Plant, who has the other remaining world title.

There are other legitimate contenders at 168. David Benavidez, in particular, is far more capable than Yildirim. He will fight Ronald Ellis on March 13; the winner will be the mandatory challenger for Canelo’s WBC belt. Jermall Charlo could decide to move up from middleweight. David Morrell, a super middleweight with a fringe “interim” title belt, is continuing to develop. Golovkin, who turns 39 this year, still wants a third fight.

Those other matches can wait for later on. Right now, there are two stops left on the road to becoming the undisputed super middleweight champion. That wouldn’t be the end of the road, however, but rather another landmark achievement. It won’t be surprising if his journey continues, if he adds new destinations along the way. What fuels Canelo Alvarez, after all, is his drive for greatness.

The 10 Count

1 – Some of the biggest news last week took place outside of the ring. The upcoming title bout between lightweight champ Teofimo Lopez and mandatory challenger George Kambosos Jr. went to a purse bid after the fighters couldn’t agree to a deal, mainly because Lopez wanted to be paid more than the minimum called for under his contract with Top Rank.

Top Rank bid more than $2.3 million for the right to stage the fight. Matchroom Boxing bid more than $3.5 million. And both of them were blown away by the bid from Triller, the social media company that was behind last year’s big Mike Tyson-Roy Jones Jr. pay-per-view success. Triller’s bid was more than $6 million.

That money will be split 65-35 between Lopez and Kambosos. Their respective promoters will get a cut of the fighters’ checks.

And yes, purse bids and paychecks do deserve our coverage and attention.

The money that boxers earn, the money that promoters and networks pay, the revenue that events pull in, all feed into whether fights can be made. Some disputes can lead to fighters sitting on the sideline, like Mikey Garcia and Andre Ward did, or to fighters buying their contracts and becoming huge superstars, like Floyd Mayweather Jr. did, or suing their way to freedom and flexibility, as Canelo Alvarez did.

There’s a lot more that can be said written about the future situation between Lopez and Top Rank. Much of it is speculation and will be shaken out over time, if and when Lopez gets by Kambosos.

But beyond that, here are some other key things I’m curious about:

– Is the kind of money that Lopez wants, and which Triller is paying, sustainable in the long run? Or is this a bubble that will wind up correcting itself?

– What kind of audience will the Lopez-Kambosos card get? It is expected to be featured alongside a main event featuring someone from the social media or celebrity realm.

Daniel Jacobs Vs Canelo Predictions

– How much of that new audience will continue to follow Lopez in the future?

– Will other fighters try to reap the same rewards that Lopez did?

– Will this change the model for how much promoters pay fighters against certain levels of opposition at certain points in their career?

2 – Triller spent more money on one undercard fight than most promoters spend on their entire pay-per-view undercard.

3 – This is a huge month for women’s boxing.

This Friday, Claressa Shields will headline a pay-per-view against Marie Eve Dicaire in her quest to add the undisputed 154-pound championship to her collection. Shields, who won two gold medals in the Olympics, has gone 10-0 as a pro, becoming a unified titleholder at 168 and then the undisputed champion at 160.

Every single fight on her pay-per-view will be a woman’s boxing match.

Also on Friday, Estelle Yoka-Mossely will fight on ESPN+. She won gold in the 2016 Olympics.

On March 13, Jessica McCaskill will face Cecilia Braekhus in a rematch as the co-featured bout to the highly anticipated rematch between Juan Francisco Estrada and Roman Gonzalez on DAZN. Last year, McCaskill upset Braekhus to seize the undisputed 147-pound championship.

A week later, Anabel Ortiz will defend her strawweight world title against undefeated contender Seniesa Estrada on the March 20 undercard of Vergil Ortiz vs. Maurice Hooker on DAZN.That same day in Mexico, junior featherweight contender Jackie Nava is scheduled to meet Karina Fernandez.

And on March 25, an NBC Sports Network show will feature Amanda Serrano (who’s won world titles in seven weight classes) defending her featherweight belts against Daniela Romina Bermudez (who’s won titles in three weight classes).

4 – There was both so much and so little at stake in the heavyweight fight between Zhilei Zhang and Jerry Forrest on the Canelo-Yildirim undercard.

Zhang came in as an undefeated heavyweight who stands 6-foot-6 and is vying for a big fight, including potentially trying to lure Anthony Joshua into a match in front of a huge stadium crowd in Zhang’s native China. The two have a shared history: Joshua defeated Zhang by decision in the 2012 Olympics and went on to win a gold medal.

And time is running out for Zhang, who turns 38 this May.

Forrest, meanwhile, has come up short every time he’s stepped up against a better quality of opponent. He suffered a pair of defeats very early in his career to Gerald Washington and Michael Hunter, both of whom were prospects at the time. Forrest dropped a debated split decision to unbeaten Jermaine Franklin in 2019. And he lost on the scorecards to former title challenger Carlos Takam last year.

He needed a good performance against Zhang, even in lieu of a win.

It quickly became clear that neither man has a bright future in the heavyweight division. Forrest has got guts but limited talent. Zhang has size and flashed some decent hand speed but lacks the stamina and tools needed to compete at a higher level.

And yet it was compelling at times to watch. Zhang knocked Forrest down three times: once apiece in rounds one, two and three. But Forrest survived, steadied himself and began to outwork Zhang. The fight went from dramatic to dreary as both fighters tired out, with plenty of clinching and leaning.

And then it went from dreary back to dramatic again. Forrest hurt Zhang in Round 8, had him badly wobbled in Round 10, but couldn’t put him away. The fight went to the scorecards, and surprisingly the judges got it right, ruling the bout a majority draw.

Forrest left the ring celebrating as if he had won. And could you blame him? The dude was down three times and didn’t lose.

5 – The pantheon of legends: Juan Manuel Marquez. Wladimir Klitschko. Jerry Forrest.

6 – Zhang’s advisers believe that the heavyweight may have been severely dehydrated.

“It was apparent to us that Zhang was not himself in the second half of the fight,” wrote Terry Lane, who advises Zhang alongside his brother, Tommy. They are the sons of famed boxing referee Mills Lane.

Daniel Jacobs Vs Canelo Predictions Week 2 2018

“He had a good training camp that included high quality sparring sessions,” Lane wrote on Sunday. “But in the locker room afterward, we noticed some concerning symptoms and took Zhang to the hospital, where he will spend a couple of nights. The good news is that all of his neurological scans are clear. However, he is suffering from anemia, high enzyme levels, and low-level renal failure.”

I’m reminded of how Bermane Stiverne was hospitalized after his first fight with Deontay Wilder in 2015, diagnosed afterward with a condition called rhabdomyolysis.

“He wanted to be at a certain weight. We made mistakes as a team,” Stiverne’s then-manager, Camille Estephan, told me about two months after that loss. “He was in a sauna room for a little too long and he was dehydrated badly. Thank god he’s OK. His health was in jeopardy. He was in a hospital for a couple of days getting rehydrated through an IV. It was serious. It wasn’t the Bermane that we know that was in the ring that night, unfortunately.”

7 – Last week, Sports Illustrated’s executive editor — the highly respected L. Jon Wertheim — published a well-written piece about social media personalities Jake and Logan Paul competing in the ring, including the postponed exhibition between Logan Paul and Floyd Mayweather Jr.

The piece rightly noted the success that sideshows have found, in contrast with the way the sport of boxing has otherwise struggled to build and maintain an audience: “The Mayweather- Paul tale of the tape — comically ill-matched as it might be — is also the tale of the entire sport. For decades now, boxing has been a study in dysfunction,” Wertheim wrote.

Daniel Jacobs Vs Canelo

I can’t argue that. But I must say that my eyebrows were raised that Sports Illustrated, the storied institution, one that put forth some of the best boxing coverage for decades, had nearly 1,600 words last week about boxing sideshows and absolutely none about Oscar Valdez’s knockout of Miguel Berchelt. I didn’t see any preview pieces either about Valdez-Berchelt, which was one of the most anticipated fights so far in 2021.

That’s not the fault of either of the SI writers who do a very good job with their boxing coverage. It’s just that they have multiple beats — they don’t just cover boxing — and are working for a publication that has a much smaller staff these days.

Chris Mannix’s other beats for the publication include the NBA, which is in-season right now. (Mannix did cover Berchelt-Valdez for a Sports Illustrated podcast and in a segment on his DAZN show with Sergio Mora.) Greg Bishop writes excellent extended features for Sports Illustrated about several sports, including boxing, continuing a long tradition of having some of the magazine’s best writing being about The Sweet Science.

I understand why SI covered these sideshows and what it means about the business of boxing. That’s an ongoing storyline worth explaining. It’s just amusing that Sports Illustrated, in essence, lamented the situation while perpetuating it.

8 – So. Many. Sideshows.

Last year brought the pay-per-view success of Mike Tyson (54 years old) in an exhibition vs. Roy Jones Jr. (51 at the time). There were also the local comebacks of aged former titleholders like Sergio Martinez (45 at the time) in Spain and Felix Sturm (41 at the time) in Germany.

Now we have Oscar De La Hoya (48) getting a boxing license again. Former junior lightweight titleholder Jorge Barrios (44) had his fourth fight since serving prison time for killing a pregnant woman and her unborn child during a hit-and-run crash in Argentina. Sam Soliman (47) is returning this month in Australia.

Pending commission approval, Antonio Tarver (52), who hasn’t fought in more than five years, could face former UFC champion Frank Mir in a boxing match on the undercard of the Jake Paul-Ben Askren circus, according to ESPN.com. I’m guessing there won’t bedrug testing for that one.

Even Julius Long, the 7-foot-1 heavyweight journeyman nicknamed “The Towering Inferno” and who aptly often went down in flames, is still fighting on at 43 years old, making an appearance in New Zealand on the undercard of Joseph Parker vs. Junior Fa. Long, who was getting knocked out by guys like Tye Fields back in 2003, is 4-18-1 in the past 15 years.

9 – Everybody wants to be Mike Tyson — including junior middleweight Gabriel Omar Diaz, who you’d never have heard about had he not been disqualified for biting Alejandro Luis Silva in the third round of their fight Saturday in Argentina.

The incident came during a clinch — the video is available here — as Silva had Diaz in a bit of a front facelock and then leaned over to put his weight on Diaz’s back. This went on for nearly five seconds until Diaz decided to be naughty, or perhaps we should say he was gnaw-ty. Silva let out a yelp, held out his left forearm, and showed the referee the mark that Diaz had left behind.

It’s fair to say that Diaz is leading the Bite of the Year nominees. Or maybe we should call them the nom-nom-nominees.

Daniel Jacobs Vs Canelo Predictions Kovalev

If he wins, we’ll name Diaz the pound-for-pound chomp-ion…

10 – Yes, that was Salt Bae who visited Canelo in his dressing room before the fight.

No word on whether they discussed contaminated meat…

Follow David Greisman on Twitter @FightingWords2. His book, “Fighting Words: The Heart and Heartbreak of Boxing,” is available on Amazon.